ROMA INTERROTTA # 1

In attesa di inserire (prossima settimana) la recensione della riedizione del catalogo di Roma Interrotta, pubblicato in occasione della mostra attualmente ospitata al MAXXI di Roma. Penso di fare una cosa utile proponendo il testo di Léa-Catherine

Szacka pubblicato su Rome, Postmodern Narratives of a Cityscape, frutto di una ricerca svolta nell'ambito del suo soggiorno Romano All'accademia Britannica. Léa ripercorre con estema precisione tutta la storia della mostra, dalla sua concezione alla realizzazione, la ringrazio per avermi permesso di pubblicare in una forma ridotta il suo saggio.

Rome, Postmodern Narratives of a Cityscape

Editors: Dom Holdaway and Filippo Trentin

Editors: Dom Holdaway and Filippo Trentin

Pickering & Chatto Publisher 2013

Until the mid-twentieth century the Western imagination seemed intent on viewing Rome purely in terms of its classical past or as a stop on the Grand Tour. This collection of essays looks at Rome from a postmodern perspective, including analysis of the city's 'unmappability', its fragmented narratives and its iconic status in literature and film.

POSTMODERN ROME AS THE SOURCE OF FRAGMENTED NARRATIVES

by Léa-Catherine

Szacka

It is comprised, not of proposals

for urban planning, naturally, but of a series of gym- nastic exercises for the

Imagination whose course runs parallel to that of Memory.

G.

C. Argan1

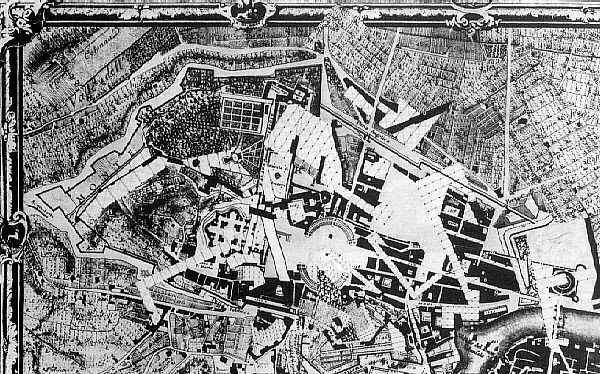

During the late 1970s a group of

twelve architects – Piero Sartogo, Colin Rowe, Robert Venturi with Denise

Scott Brown, Michael Graves, Costantino Dardi, Antoine Grumbach, James

Stirling, Paolo Portoghesi, Romaldo Giurgola, Robert Krier, Aldo Rossi and Léon Krier –

were brought

together for an exhibition that redrew Giambattista Nolli’s 1748 map of Rome and sought to use this reinter-

preted map in the production of visionary drawings of architecture and

urbanism.

Nolli’s map was the first attempt to produce a complete

outline of Rome, his adoptive city. Created under the commission of Pope

Benedict XIV, the map, entitled the ‘Nuova Topografia di Roma’ (New

Topography of Rome), has since become an important and highly influential

representation. The city itself was represented in twelve connected segments,

and the map’s frame was an archi- tectonic–allegorical

capriccio that represented the two Romes: on the left, the antique (and pagan)

Rome, on the right, the modern (and sacred) one. It was commissioned to be a

precise technical work, intended by the pope as a rational outline of the city’s social and legal administration. As Michal Graves

notes,

The vast housing and commercial

stock of the city was rendered as urban poché, while the religious and state structures were described in a level of

detail which encourages the understanding of the city as a spatial sequence of

successive rooms.2

The ‘Topografia’ also provided an immediate and intuitive understanding

of the city’s urban form through the simple yet

effective graphic method of rendering solids as dark grey (with hatch marks),

and rendering voids as white or light shades of grey to represent terrain such

as vegetation or paving patterns. By adopting this iconographic approach –

one of the

first maps of the city designed in this way – Nolli (who was not an architect,

but a surveyor) sought to offer a street map that was legible in what was,

quite interestingly, posited as an objective manner, offering a new

awareness of the city by emphasizing its internal and external voids.

The new map of Rome represented a

synchronic–historical section of the pre-industrial, Baroque city

at the peak of its splendour.3 What remains striking today about Nolli’s blueprint is the intrinsic similarity that it

illustrated between the ancient cityscape and that of pre-modern Rome, which

had changed rela- tively little (and certainly remained within the Aurelian

Walls).4 It moreover caught that historical moment that

signalled the potential for significant change: soon after the map was

produced, the city was to face the major urban upheavals ordered in the

nineteenth century by King Victor Emmanuel II and King Umberto I, and in the

twentieth century by the fascist regime. For both its innovation and its

synchronic snapshot of this historical moment, the map’s significance endured, and in fact from the late

1950s to the late 1980s, the re- appropriated Nolli map had become the paradigm

of modern urban planning – especially in American circles.5

During that same latter period, the

significance of Nolli’s map surged

when a Roman non-profit art organization invited a panel of internationally

renowned architects, those named above, to develop one of the twelve segments

of the map into a personal critique of the city’s development in the nineteenth and twentieth century.

The result, twelve disjointed narratives that signalled the fragmentariness of

the ‘Eternal

City’, was exhibited in Rome’s Trajan Markets in 1978 under the title ‘Roma Interrotta’ (Rome Interrupted).

In spite of its playful nature and

form, as I will argue in the following para- graphs, the exhibition embodied

and reflected the tensions of the postmodern condition under which it was

forged: from the interruption of the city’s singu- lar grand narrative and the impossibility of

objective–realistic representation, through to the fragmentation

of the urbanscape and the shattering of objectivity.

Despite some recent scholarly and

museological attention,6 ‘Roma

Interrotta’ remains

notably understudied. By combining close readings of the original draw- ings

produced for the exhibition and analysis of archival material related to the

organization of the event with an oral history campaign conducted in the fall

of 2010,7 I aim to shed new light on the history of this unique

and significant event. As I will show, by proposing a non-chronological and

non-linear image of Rome, ‘Roma Interrotta’ produced twelve contextualized yet highly individual-

istic endeavours that correspond to that shift towards a narrative of

fragmented and plural subjectivities that is typical of postmodernity. I do so

by scrutinizing the genesis, organization and realization of the exhibition in

relation to questions of pastiche and history in the first section; and, in the

second, by honing in on three specific contributions that very fruitfully

illustrate a shift in architectural and artistic thinking, from a unitarian and

objective truth to a subjective multiplicity.

The Exhibition Space and

Reappropriated History

Embedded in the artistic, political

and social context of late 1970s Italy, ‘Roma Interrotta’ encapsulates the atmosphere of a very specific epoch.

It was an unconventional type of architectural exhibition, organized by the

Incontri Internazionali d’Arte (IIA,

International Art Meetings), a non-profit organiza- tion and an underground

critical workshop of the avant-garde that had, since the start of the 1970s,

been very active on the contemporary Roman art scene. One of the main tenets of

this organization was to engage with all forms of art and thus to break down

the barriers between disciplines. The founder and general secretary of the IIA,

Graziella Lonardi Buontempo, was described as a ‘passionate

cultural force in Rome since the early 1970s’ and a ‘tireless

promoter of advanced artistic research, organizing great public exhibitions and

promoting a new approach to culture’.8 During the 1970s, Lonardi Buontempo

interacted directly with many Italian and international artists such as Andy

Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Alighiero Boetti, Mario Merz and Jannis Kounnellis. With

the help of the curator and critic Achille Bonito Oliva, she promoted new forms

of artistic creativity and performances by creating a ‘place of

experimentation, where artists and critics interacted with the public in

performances and discussions’.9 Lonardi Buontempo and Bonito Oliva’s exhibitions – their most

celebrated and revo- lutionary artistic events being ‘Vitalità del negativo nell’arte italiana 1960/70’ and ‘Contemporanea’ – were famous

for their choice of venues, often unusual and unconventional public spaces.10 Following on

from these experiments, the IIA decided to hold the ‘Roma Interrotta’ exhibition in

the archaeological space of Trajan’s Market. At

the time, the space of the disused market was practically unknown to the public

(both tourists and Romans). Thus the choice of this par- ticular exhibition

space adhered to the contemporary desire to retrieve historical and collective

memory, thus guaranteeing the exhibition a permanent and ‘real’ impact on the

destiny of Rome’s city centre.

In the particular case of ‘Roma Interrotta’, not only were the discourses and content of the show

innovative, but also the container and the exhibition design –

projected by

Franco Raggi – made a highly postmodern repertoire of forms and

ideas. Raggi, a young designer, director and managing editor of the magazine Modo, and previously editor at Casabella, had already organized or co-organized important

exhibitions at the Milan Triennale (‘Architettura-Città’ with Aldo

Rossi, 1973) and at the Venice Biennale (‘Europa-America’ with Vit- torio Gregotti, 1976), where he was asked to

work on ‘Roma

Interrotta’. For Raggi, the exhibition had a

strong ‘surreal’ component,

something that he chose to emphasize in his design, using references from

popular culture (‘the pop’) and

allusions to ecclesiastical and ceremonial traditions.11 It was a

matter of surpassing the classical architecture exhibition by playing on

languages. The exhibition venue, Trajan’s Market, was ancient Rome’s centre for commerce and communication. It was thus a

highly ‘functional’ space. The street’s entrance on Via IV Novembre was marked by a very dry

and heavy arch that almost predated rationalist architec- ture. Inside was a

central space with six shops on each side. Emphasizing what used to be the

commercial function of the building, Raggi gave each architect a shop in which

to exhibit his work, creating an historical overlap between the market’s original typology and its new function as an exhibition

space.

In addition to their 65 by 46 cm

section of a revisited Nolli map, each archi- tect produced a variable number

of images to be exhibited in their own small space. Yet because of technical

constraints, their material had to be hung with- out ever touching the

structural walls of the market. Raggi thus imagined an innovative support

system: a series of pale blue grid structures made of light- weight wood and

hung from elements that had been left behind after previous exhibitions. In the

central space were the old 1748 Nolli

map and the new 1978 ‘interrupted’ one. Set one

against the other (over the palimpsest of earlier exhibi- tions), the two maps

generated a physical space, a cube, raised on a fake marble base and preceded

by a red carpet, in which visitors could stand. Inside the cube were the maps,

while outside were inscriptions in golden letters: on the one side the names of

the twelve exhibitors, and on the other ‘Giambattista Nolli, Pianta di Roma 1748’. And as a majestic gesture recalling the metaphysical

paintings of de Chirico, Raggi planned an extravagant announcement of the title

‘Roma

Interrotta’ by creating

an urban sign, a 300 square metre electric blue satin cloth –

similar to

one employed in religious ceremonies – that would

float in the arti- ficial breeze produced by a two-metre wide fan from Cinecittà. Raggi’s design used several tropes of postmodernism: it

recalled the history of the building; it played with a mix and match of rich

and poor material (mixing gold letters, red carpet, fake marble and shiny blue

fabric with the ruins of the old market and some lightweight wood structures);

it mingled the sacred (the fabric and the golden letters were reminiscent of

the material traditionally used in the church) and the profane (the market),

the banal and the extraordinary; it based itself on a series of signs (such as

the blue canvas) and in so doing it became both a critical statement and an

urban event.

The Interrupted City

Though originally intended as the

first event in a series, ‘Roma

Interrotta’ was

ultimately the only IIA exhibition ever dedicated specifically to urbanism and

architecture.12 But in its unconventional (at least for the time)

collaboration between an art organization and a group of architects reflecting

on urban prob- lems, ‘Roma

Interrotta’ triggered a

curious relationship between the architects and their forms of representation

(here, principally drawing). The maps and architectural representations of

all forms and materials were, of course, produced only for the sake of being

exhibited.13 And yet, by being solely created by archi- tects, the

exhibition fostered the idea of the architect’s autonomy as put forward by Aldo Rossi and some of

the other rationalist architects. Though space pre- vents an extensive comparison,

this tense interplay between the practical and the representational undoubtedly

invokes a reading of the exhibition as comment on Rome as ‘Thirdspace’. This follows Edward Soja’s notion of ‘Firstspace’ and ‘Secondspace’: ‘Thirdspace

... can be described as a creative recombination and extension, one that builds

on a Firstspace perspective that is focused on the “real” material

world and a Secondspace perspective that interprets this reality through “imagined”

representations

of spatiality’.14 Introducing this intrinsic multi-sta- bility of the

city in ‘Roma

Interrotta’ is an

important step in understanding the importance of this conception of postmodern

Rome.

What was the role and place of ‘Roma Interrotta’ within the

larger history of postmodernism? The Anglo-American architectural historian and

critic Charles Jencks has famously argued that modernism died in 1972, with the

destruction of Pruitt-Igoe housing estate in St Louis, Missouri. Following

that, in 1977, postmodernism was almost immediately codified and disseminated

with the publication of Jencks’s first

edition of The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. Yet it was soon

after, in 1980, that the Venice Architecture Biennale marked a watershed moment

between ‘the end of the beginning’ and ‘the beginning

of the end’ of

postmodernism. Steven Connor distinguishes four different stages in the

development of postmodernist architecture: accumulation, through the 1970s and

the early part of the 1980s; synthesis, from the middle of the 1980s onwards;

autonomy, from the beginning of the 1990s and dissipation later in the 1990s.15 If we follow

Connor’s temporality, chronologically at

least, 1977–8 would cor- respond to that early stage of

postmodernism during which the hypothesis was under development by people like

Jencks, but also Daniel Bell, Jean Baudrillard, Jean-Francois Lyotard and Ihab

Hassan.

The changing perspective on the

city, a perspective associated with post- modernism, in reality started to

occur around 1966, with the publication of two seminal books: Complexity and

Contradiction in Architecture by Robert Venturi and L’architettura della città by Aldo Rossi.16 While the

former served as a vir- ulent critique of modern architecture and urbanism, the

latter advocated the return to the traditional city, insisting on the

importance of the notion of place and monuments, and arguing that the city was

the locus of collective memory. Rossi was

also innovative in his suggestion of a new relation between urban analysis and

architectural projects. Following that, the aftermath of the revolts of 1968

led to important changes in decision-making policies and a renewed interest in

the question of urbanity in many countries (mainly France, Italy and the USA).17 In Rome, for

instance, the election in 1976 of the art historian

Giulio Carlo Argan as the first

leftist mayor gave rise to a series of artistic experi- ments funding

historical monuments in public places in an attempt to alter the sombre

atmosphere in the wake of the anni

di piombo (years of

lead). Argan endorsed Renato Nicolini’s Estate Romana (Roman

Summer), a famous cultural manifestation consisting of a series of ephemeral

cultural manifestations – big cinematographic, theatrical or musical events –

that took

place in various monu- mental loci of the capital from 1977 onward.

The architects of ‘Roma Interrotta’ adopted a new

attitude towards urban design that was part of a broader historical shift. They

perceived the city as a field where they were allowed to ‘play’, either using a strong analytical method- ology,

borrowing from sociological studies and learning from observing what was there,

or interweaving historical chronicle with fictionalized narratives and fables.18 ‘Roma Interrotta’ can be seen

as part of that larger cultural phenomenon which from the late 1960s had

proliferated in architectural circles, each one con- taminating the other, and

leading to a definition of the city that was no longer merely a functional

organism with transportation network or a series of func- tional zones (as described

and promoted in the CIAM 1933 Athen’s Chart), but

rather as the product of human culture.

On the occasion of the exhibition,

Argan wrote that ‘Rome was an inter- rupted city because there came a

time when it was no longer imagined, and it began to be planned (badly)’.19 It was in

reaction to this particular state of affairs described by Argan that the

Italian architect Piero Sartago together with the cul- tural institution Incontri Internazionali d’Arte, proposed to

step back 230 years and to draw inspiration from the Nolli map. For the purpose

of the exercise, architects ‘added to,

subtracted from, altered, or destroyed the Rome of 1748 to show the city as it

might have been’. And since the Nolli map had

originally been divided into twelve tables of engravings, due to printing

limitations, noth- ing was easier than to distribute the twelve sections

between the participants. As suggested by Thomas Weaver, the result, presented

in ‘Roma

Interrotta’, was an assemblage of

heterogeneous projects, a map of adjacency, which initiated an altogether new

and radical way of approaching Rome’s urban design.

The modus operandi of ‘Roma Interrotta’ included a very strong historically speculative and

imaginative component: the aim was to imagine ‘una nuova Roma’ (a new Rome), as though the city had not changed in

more than 200 years.20 In other words, it was a matter of going back to the

pre-modern city by fictively erasing all the problematic urban transformation

that had been imple- mented in order to create a more modern and more

functional city.

The ‘Roma Interrotta’ project sprang from a particular theoretical and

methodological premise: what the Anglo-Saxon architectural historian Colin Rowe

has called ‘design speculations and fantasies on historic city

plans.’21 The technique

of ‘what might have happened’ was directly

related to Rowe’s way of

thinking.22 One of the

main figures of the critical revisionism of the Modern movement in architecture

and urban design, Rowe’s early work

at Cornell Uni- versity led to the Contextualist school of thought. This body

of thought was critical of modern urbanist and architectural theory of design

wherein modern building types are harmonized with urban forms common to a

traditional city.23 As J. Stevens Curl explains, over the course of a

brilliant and very influential academic career Rowe focused on developing an

alternative method of urban design that derived in part from the earlier work

of Camillo Sitte, and was based on the creation of cities through a process of

collage and superimposed pieces.24 From the early 1970s onwards, Rowe started to make

public his contextualist thinking on the city, publishing articles that would

eventually become Collage City, a book

published in 1978. In Collage City, Rowe

proposed bricolage as an alternative

to the scientific methods of planning put forward by rationalist modernist

planners and architects. For Rowe, collage acts as an antidote to the mental

structures responsible for the totalitarian excess.25 Also very

prominent in the book was Rowe’s

condemnation of the disappearance, in the modern city, of the collective space

of the street or the public place.

The interesting question that

remains is: how did the contextualist ideas travel from Ithaca to Rome, and

eventually influence the modus operandi of ‘Roma Interrotta’? In the late 1960s Sartogo was invited to Cornell

University, where he visited Rowe’s

contextualist urban design studio on several occasions.26 The Roman

architect moreover had frequent contact with the New York’s Insti- tute of Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS)27 and in

particular with Peter Eiseman, with whom, in 1971, he had put together a

special bilingual issue of the magazine Casabella

– the first ever published –

with the

title ‘The City as an Artifact’.28 In the introduction

to the issue, Alessandro Mendini, then editor of Casabella,

wrote: ‘we resolved that Europe should hear of these ideas –

ideas which,

in the US, had already brought about approaches to planning radically different

from orthodoxy practice and had grafted on as yet unexplored criteria of

expressivity’.29 Thus, when Graziella Lonardi Buontempo and the IIA

sought the collaboration of Sartogo to organize an exhibition on the city of

Rome, Sar- togo drew on the work done for the Casabella’s bilingual issue and developed the idea of the ‘artefact’. As Sartogo himself has explained,30 the ‘Roma Interrotta’ project allow

architects to imagine what the city of Rome would look like if the Tiber’s embankments had not been built, thus destroying this

direct connec- tion between the river and the urban fabric.31 In the same

way, this synchronic approach permits architects to speculate on what Rome

could have become if the fascist regime had not destroyed the historical urban

fabric of vast portions of the historical city centre.32

Fragments and

Subjectivities

The primary aim of the ‘Roma Interrotta’ project was

to find ways of revisiting Rome by means of a critical assessment that took the

form of a giant collage – that is, a conjunctive operation using ‘both/and’ rather than a

disjunctive one using ‘either/or’. This

approach was inspired by Colin Rowe’s own, which

in turn was influenced by Claude Lévi-Strauss’s notion of the collage as a mental struc- ture, and

one that could serve as an antidote to the totalitarian drift.33 It may also

have owed something to the cadavres exquis, a famous surrealist game played

by André Breton and his colleagues: a method by which a

collection of words or images is cooperatively assembled by a group of

collaborators. Yet there was one major difference between the two endeavours:

if the technique of cadavres exquis implied that each participant should add to a

composition in sequence, either by following a rule or by being allowed to see

the end of what the previ- ous person contributed, in ‘Roma Interrotta’ no place was

left for collaboration as each architect was responsible for a single piece of

the puzzle, without any preparatory group effort or consultation.

Unlike the surrealist image, ‘Roma Interrotta’ was not only

concerned with the pictorial design. It was, contributor Antoine Grumbach

notes, concerned with the question of the ‘future of the

city’s past’.34 And while all

participants agreed that the form of future cities should be deduced from

history, the responses were of an extremely diverse nature. Offering a

multifaceted interpre- tation of the Nolli map and giving to the city as many ‘fictional’ meanings as

possible, ‘Roma

Interrotta’ fostered the

typical postmodern spirit of pluralism and tolerance –

as strongly

defended by Charles Jencks in his Language of Post- Modern Architecture,

as well as by Venturi and Scott Brown.

In ‘Roma Interrotta’, rather than

producing an overall and unified result, what really mattered was to show many

approaches to the problem of the historical city centre: the aim was to push

the architects to produce a set of drawings that would exemplify their own view

of the city or what the city meant to them, while liberating designer

creativity, freeing them of any sort of constraints. In the fol- lowing

paragraphs, I focus on the output of three of the twelve ‘Roma Interrotta’ proposals:

those of Antoine Grumbach, Léon Krier and

James Stirling. Though quite evidently each project brings its own artistic

merit and value to the discus- sion, these three projects have been selected

for their relevance to the idea of a shift towards pluralism and subjectivity,

whereby each project proposes a personal language, at times megalomaniac, at

times deeply introspective and poetic. Rather than being pseudo-objective, the

projects elaborate a series of individual rules or logics based on historical,

archeological or almost anthropological research.35

Conclusion: The Future of the City’s

Past

The Roman exhibition closed down on

27 June 1978 after attracting around 20,000 visitors. Despite some bitter

criticism, the ‘Roma

Interrotta’ drawings came

to be in demand across the globe and went on an impressive international tour

that lasted thirty years.36

In July 1979, Ada Louise Huxtable

published a review of the exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Museum. Although

criticizing the show for being ‘an elite and

erudite game’ as well as an

‘obscure, technical, parochial, and private’ endeavour,

she wrote that the results of the undertaking were ‘as

interesting for the professional as they are baffling to the layman’. Huxtable declared: ‘this is one

of these studies that has already became legend, the kind of theoretical

exercise that takes a permanent place in the more esoteric annals of art and

architec- ture history’.37 Defending a similar position, Giorgio Muratore, in a

text entitled ‘Dodici

architetti ai Mercati Traianei giocano con Roma’ (Twelve

Architects Play with Rome Trajan’s Market),

published in the daily newspaper La Repub- blica, strongly deplored the fact that

the exhibition had been used as

pretesto

... per un confronto diretto tra architetture antiche e architetture moderne

nell’ipotesi decisamente snob e tipicamente radicale di un corto

circuito culturale che, annulati più di duecento anni di storia, desse vita ad una

conflagrazione di linguaggi, di materiale e di tecniche capace di simulare una

virtuale alternativa ai drammatici fatti reali della vicenda edilizia contemporanea

romana in particolare.38

(the pretext for a direct

confrontation between antique and modern architecture in a definitely elitist

and typically radical hypothesis of cultural short circuit. It deleted more

than 200 years of history in favour of a conflagration of language, material

and technique, capable of imitating a virtual alternative to the dramatic real

facts of the situation of contemporary construction, particularly in Rome.)

The critic went on to suggest that

the show looked like a sort of bal masqué where every

architect read its own part with a tragic determination.39 According to

Muratore, only a few of the contributing architects remained lucid and appre-

ciated that ‘Roma

Interrotta’ was nothing

more than a complex and gigantic architectural game. And according to the

architectural historian Francesco Dal Co, the exercise was very academic and

the project had obviously been imagined only to be exhibited.40 All these

critics refer to the artistic aspect of the endeav- our, questioning its true

contribution to the architectural field.

However, the impressive tour of the

‘Roma

Interrotta’ project

raised ques- tions about the international impact that the individual

contributions may have had on the imaginaries of architects and urban planners.

The ‘Roma

Interrotta’ drawings were

undoubtedly seen by a massive number of people. Confronting visitors with a

rich repertoire of languages and representation techniques, the set of drawings

of ‘Roma

Interrotta’ somehow

symbolize a double paradigm shift: on the one hand, the newly acquired freedom

of the architect, and, on the other, the entry of architecture into cultural

institutions. Yet ‘Roma

Interrotta’ was also, by

touring all over the world, an excuse to circulate a new image of the city of

Rome. No longer seen as simply as the one dimensional historical city, Rome was

now viewed as a repertoire of postmodern urban and architectural forms with

which architects could play and which gave weight and value to their work.

‘Roma Interrotta’, then,

offers a postmodern image of Rome, presenting the ‘Eternal city’ as a diffuse

and disorientating place that challenges the notion of a unitarian territory

produced by a single overarching plan. The event was the occasion to

materialize and make more ‘public’ an ongoing shift with regard to urban planning: a

shift towards a more subjective approach to the city. For the endeavour,

architects took as their departure point a past that was no longer there,

intermingling that state of affairs with a future that was purely fictional or,

at least, not yet present. As such, ‘Roma Interrotta’s modus operandi corresponds perfectly

with Steven Connor’s definition

of postmodernism as

that condition in which for the

first time, and as a result of technologies that allow large scale storage,

access, and reproduction of records of the past, the past appears to be

included in the present, or at the present’s disposal, and in which the ration between present

and past has therefore changed.41

That new sort of temporality

transformed the city by concretizing the rehabili- tation of old industrial or

commercial structures (such as Trajan’s Market) in containers for cultural activities.

‘Roma Interrotta’ was, first and foremost, an excuse to stage practices

and generate a unique set of drawings which travelled the world, triggering

debate and discussion. Rather than the overall result, what really mattered in ‘Roma Interrotta’ was to show

one’s approach to the problem of

historical city centre. While the group with its associate ideology was very

important, the figure of the architect as a ‘super hero’ artist and

intellectual was also starting to emerge at precisely that time. By taking part

in ‘Roma

Interrotta’, architects produced a series of

drawings which, through a sort of narcissistic process, contributed to their

own personal language and techniques while blowing up their ego (as exemplified

by the exhibition’s engorged blue cube containing, on

the inside, the Nolli map

and the new map of Rome, and on the outside, the names of the twelve architects

written in big golden letters). ‘Roma Interrotta’ is exemplary of the postmodern period: it shows an

architecture based on the notions of ‘event’ and‘mediatization’,whichsuddenlytookovertheculturalindustry;itgenerated

more than a hundred original drawings or images that depicted the urban

condi- tion as much as it did the personality of each architect. Like many

postmodern enterprises, it was the images generated by ‘Roma Interrotta’ rather than

the pro- jects themselves, which really influenced the architectural world.

On 20 December 2010 Graziella

Lonardi Buontempo died at the age of eighty-two. The (almost) complete set of

drawings produced on the occasion of the legendary exhibition were in

possession of Lonardi Buontempo, who left no clear directions as to what should

be done with them, provoking a frantic competi- tion between different cultural

institutions that sought after the drawings. Though this raises many further

questions about the precise financial and cultural value of the exhibition, the

drawings are testament to the specific crossover of historical instances and

fragmented subjectivities and continue to provide an extraordinarily valuable

key to understanding the Italian capital’s postmodern foundations.

Notes

1. J. Franchina (ed.), Roma Interrotta,

trans. J. Franchina (Rome: Incontri Internazionali d’Arte/Officina

edizioni, 1979), 208, p. 12.

2. M. Graves, ‘Roman

Interventions’, Architectural Design, 49:3–4, Profile

20, (1979), p. 4.

3. M. Bevilacqua (ed.), Nolli, Vasi, Piranesi: Immagine di Roma Antica e Moderna [Nolli, Vasi, Piranesi: Images of Ancient and Modern Rome]

(Rome: Artemide Edizioni, 2004), p. 12.

4. See Marco Cavietti’s contribution to this volume for a broader discussion

of the city’s expansion outside these perimeter

walls, pp. 19–37.

5. See A. P. Latini in

Bevilacqua (ed.), Nolli, Vasi, Piranesi: Immagine di

Roma Antica e Moderna, p. 65.

6. As examples of scholarly attention compare

T. Weaver, ‘Civitas Interruptus’, in Post- modernism: Style and Subversion, 1970–1990 (London: Victoria and Albert

Museum, 2011), pp. 126–131 and M. Delbeke, ‘Baroque Rome as a (Post)Modernist

Model’, in OASE 86, pp. 74–85. As an

example of museological attention, see the exhibition ‘Roma Interrotta’ at the 11th

Venice Architecture Biennale, ‘Out There:

Architecture Beyond Building’, curated by

Aaron Betsky, 14 September to 23 November 2008. Also, on 7 September 2012 the

archive of the Incontri Internazionali d’Arte was assimilated into the collection of the MAXXI

thanks to a donation by the late Graziella Lonardi Buon- tempo of 100,000

documents and 8,000 books, including all the original documents of ‘Roma Interrotta’.

7. I would like to thank the British School at

Rome and the Giles Worsley Travel Fellow- ship, which enabled me to undertake

this research.

8. These descriptions of Lonardi Buontempo are

taken from the documentary A Roma La

Nostra Era Avanguardia: Un omaggio alle grandi mostre degli anni ’70.

Vitalità del negativo e Conteporane [In Rome,

ours was an Avantgarde. A Homage to the Great Exhi- bitions of the 70s: ‘The Vitality

of the Negative’ and ‘Contemporary’], film, directed by L. Massimo Barbero and Francesca

Pola (Italy: MACRO (Museo d’Arte Conteporanea di Roma) and

Incontri Internazionali d’Arte, 2010).

9. L. M. Barbaro and F. Pola, A Roma La

Nostra Era Avanguardia.

10. For example, ‘Contemporanea

[Contemporary]’, an interdisciplinary and

international

exhibition presented in 1973–4, was held in the new underground car park of the Villa Borghese, designed by Luigi Moretti, and the 1979 exhibition ‘Le stanze [The Rooms]’, curated by Bonito Oliva, took place in the Castello Colonna, Gennazzano, Rome.

exhibition presented in 1973–4, was held in the new underground car park of the Villa Borghese, designed by Luigi Moretti, and the 1979 exhibition ‘Le stanze [The Rooms]’, curated by Bonito Oliva, took place in the Castello Colonna, Gennazzano, Rome.

11. Franco Raggi, interview with the author, 23

November 2010.

12. ‘This cultural

event whose theme is Rome, the “capital” city, is the

first in a series of spe- cific initiatives which the Incontri Internazionali d’Arte is dedicating to urban studies’. In Franchina (ed.), Roma Interrotta,

p. 10.

13. In addition to the twelve tables of

engraving, each architect had to produce a series of graphic documents

(drawings, collage, etc.) that represented his or her ideas. The archive of the

IIA includes more than 130 graphic documents related to the ‘Roma Interrotta’ exhibition.

14. E. Soja, Thirdspace:

Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (Oxford:

Blackwell Publishing, 1996), p. 6.

15. See S. Connor (ed.), The Cambridge

Companion to Postmodernism (Cambridge: Cam- bridge University Press, 2004), pp. 1–2.

16. R. Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in

Architecture (New York: Museum of Mod- ern Art, 1966); A. Rossi, L’architettura della città [The

Architecture of the City] (Padua: Marsilio Press, 1966).

17. J.-L.

Cohen, The Future of

Architecture Since 1968 (London: Phaidon, 2012), p. 404.

18. There are many other examples of this trend,

one of the most famous being Rem Kool- haas’s retroactive manifesto for Manhattan, published the

same year as ‘Roma

Interrotta’. See R. Koolhaas, Delirious New

York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (New York: Oxford University Press,

1978) where Koolhaas proposes urbanism as a journalistic text in which urbanism

is architecture and architecture is urbanism. See H. White, Metahis- tory:

The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore, MD: Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1973).

Hopkins University Press, 1973).

19. Franchina (ed.), Roma Interrotta,

p. 11.

20. Piero Sartogo,

presentazione del progetto, at the 11th Venice Architecture Biennale,

‘Out There: Architecture Beyond Building’, Roma Interrotta, 14 September to 23

November 2008.

‘Out There: Architecture Beyond Building’, Roma Interrotta, 14 September to 23

November 2008.

21. See C. Rowe, As I was

Saying: Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays, 3 vols (Cambridge,

London: The MIT Press, 1996), vol. 3, p. 6.

London: The MIT Press, 1996), vol. 3, p. 6.

22. In 1945, Rowe had completed an MA thesis for

Professor Rudolf Wittkower at the War-

burg Institute in London, a work starting from the assumption that Inigo Jones may have intended to publish a theoretical treatise on architecture, analogous to Palladio’s Four Books. This first theoretical work established Rowe’s way of speculating and imagining what might have happened: an approach to the history of architecture that was largely imaginary and factually questionable, but which he gradually built into a vastly erudite, coherently argued way of thinking and seeing that exasperated conventional historians and became the inspiration for a generation of practising architects to consider history imaginatively, as an active component in their design process.

burg Institute in London, a work starting from the assumption that Inigo Jones may have intended to publish a theoretical treatise on architecture, analogous to Palladio’s Four Books. This first theoretical work established Rowe’s way of speculating and imagining what might have happened: an approach to the history of architecture that was largely imaginary and factually questionable, but which he gradually built into a vastly erudite, coherently argued way of thinking and seeing that exasperated conventional historians and became the inspiration for a generation of practising architects to consider history imaginatively, as an active component in their design process.

23. Rowe accepted, in 1962, a professorship at

Cornell University. There he would soon develop his own urban design studio,

aiming to reconcile modern architecture with the urban context (or what he

called the ‘theatre of memory’ in reference

to the work of Frances Yates).

24. The ideal model for this pragmatic,

anti-doctrinaire approach was the ruined villa of the Roman Emperor Hadrian at

Tivoli, outside Rome. For Rowe this villa (as opposed to the ‘perfect’ model of

Versailles) was the model of a collage, for it was a seemingly disjointed

amalgam of discrete enthusiasm in an attempt to conceal any reference to

guiding principles. See J. Stevens Curl, A Dictionary of Architecture and

Landscape Archi- tecture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 880.

25. S. Malfroy, ‘Présentation’, in C. Rowe and F. Koetter, Collage City (Geneva: In Folio, 2002), p. 16.

26. Piero Sartogo, interview with the author, 5

December 2010.

27. The IAUS was an independent research, design

and educational corporation in the inter-

related fields of architecture, urban design and planning. It was created in 1967 by the Board of Regents of the State University of New York. The aims of the institute were to propose and develop methods and solutions for problems of the urban environment; to develop a body of theory and criticism with regards to architecture, urban design and planning; to function as a forum for public criticism and debate; to amplify and develop present methods of architectural education and practice.

related fields of architecture, urban design and planning. It was created in 1967 by the Board of Regents of the State University of New York. The aims of the institute were to propose and develop methods and solutions for problems of the urban environment; to develop a body of theory and criticism with regards to architecture, urban design and planning; to function as a forum for public criticism and debate; to amplify and develop present methods of architectural education and practice.

28. ‘The City as

an Artifact’, Casabella, n. 359–60, December

1971. In this issue were assembled a sequence of hitherto unpublished articles

especially written by Alesssandro Mendini, Franco Alberti, Denise Scott Brown,

Robert Venturi, Peter Eisenman, Joseph Rykwert, William Ellis, Stanford

Anderson, Emilio Ambasz and Piero Sartogo.

29. A. Mendini, ‘The City as

an Artifact’, Casabella 359–60, (December 1971), p. 9.

30. This was in the film Roma Interrotta, presented at the 11th Venice

Architecture Biennale,

2008.

2008.

31. During the second half of the nineteenth

century, the riverbanks and road along the

Tiber were radically reconstructed to improve the city’s flooding defences and transport connections. As a consequence of that, Rome saw the destruction of many of the city’s historical places such as the Porto di Ripetta, a port designed and built in 1707 by the Italian Baroque architect Alessandro Specchi, and famous for its steps descending into the water and producing a sort of scenographic space in the city.

Tiber were radically reconstructed to improve the city’s flooding defences and transport connections. As a consequence of that, Rome saw the destruction of many of the city’s historical places such as the Porto di Ripetta, a port designed and built in 1707 by the Italian Baroque architect Alessandro Specchi, and famous for its steps descending into the water and producing a sort of scenographic space in the city.

32. Three main circulation axes were introduced

by Mussolini during the 1930s.

33. Rowe refers to C. Lévi-Strauss, La Pensée Sauvage [The Savage Mind] (Paris: Plan, 1962).

34. See

A. Grumbach, ‘Roma

Interrotta’, in J. Dethier and A. Guiheux (eds), La

ville, art et

architecture en Europe 1870–1993 [The City, Art and Architecture in Europe, 1870–

1993] (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 1994), p. 445.

architecture en Europe 1870–1993 [The City, Art and Architecture in Europe, 1870–

1993] (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 1994), p. 445.

35. Other ‘Roma Interrotta’ projects also suggest the change from objectivity to

subjectivity.

A key example is Paolo Portoghesi’s project: based on a planimetry of the physical envi- ronment of the Chia Ravine, it analyses the city by means of a series of visual analogies with naturalistic environments. Another interesting approach was put forward by Colin Rowe and his team, and was based on a totally fictitious scenario involving Vincent Mulcahy, a Jesuit scholar based in Rome. This project was described by Rowe and his team as ‘an alibi for topographical and contextual concern’ and ‘a city which represents a coalition of intentions rather than the singular presence of any immediately apparent all-coordinating idea’, see Franchina (ed.), Roma Interrotta, p. 150.

A key example is Paolo Portoghesi’s project: based on a planimetry of the physical envi- ronment of the Chia Ravine, it analyses the city by means of a series of visual analogies with naturalistic environments. Another interesting approach was put forward by Colin Rowe and his team, and was based on a totally fictitious scenario involving Vincent Mulcahy, a Jesuit scholar based in Rome. This project was described by Rowe and his team as ‘an alibi for topographical and contextual concern’ and ‘a city which represents a coalition of intentions rather than the singular presence of any immediately apparent all-coordinating idea’, see Franchina (ed.), Roma Interrotta, p. 150.

36. From October 1978 to May 1994 the drawings

(or part of the drawings) were exhib-

ited in Mexico City, London, Bilbao, New York, Toronto, Zurich, Tokyo, São Paolo and

Paris.

ited in Mexico City, London, Bilbao, New York, Toronto, Zurich, Tokyo, São Paolo and

Paris.

37. A.

L. Huxtable, ‘Rome and the Artistic Fantasy’, New

York Times, 15 July

1979, p. 35.

38. G. Muratore, ‘Dodici Architetti ai mercati Traianei

giocano con Roma’ [Twelve Archi-

tects play with Rome in Trajan’s Market], La Repubblica, 21–2 May 1978, p. 21.

tects play with Rome in Trajan’s Market], La Repubblica, 21–2 May 1978, p. 21.

39. Ibid.

40. F. Dal Co, ‘Review Roma Interrotta’, Oppositions, 12 (Spring 1978), pp. 112–13.

41. S. Condor (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to

Postmodernism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 10.